When you tend a bar, you soon learn that the later it gets, the weirder it gets, and I have had my share of weirdoes. There was that vampire romance writer a few years back – a writer of vampire romances, not a romance writer who was a vampire – and then the guy who claimed he was a special ops agent fighting monsters, and of course, the old lady who drank absinthe and crocheted quotes from Nietzsche onto throw pillows. Then there was this guy, our latest creeper, just before we got shut down. He sat at the dark end of the bar, by himself. He was tall and thin, with exaggerated features, what people used to call gaunt – a real Ichabod Crane type, but with this weird pot belly. He was a quiet sort, nursing his third scotch as we approached the last call. He hadn’t said anything about himself, didn’t really have to, the faded, crude tattoo of digits on his arm spoke volumes. I had been in the business, and in this town long enough to know when to talk to people and when to leave them alone. They all come around to talking, eventually. It’s like a church confessional, with booze, and without the guilt.

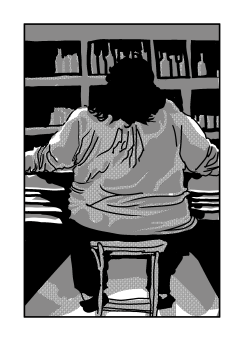

I rang the bell, “LAST CALL,” I said to no one in particular. The few other patrons I had filtered out the door. I wandered down to the dark end and poured Ichabod one on the house.

His eyes looked up from the glass and there was something haunting in them. “Do you think you’ll make a good parent?” He gestured at my belly, which was just starting to be not noticeable.

There it is, I thought. It’s confession time. “Don’t we all?”

He kept his eyes locked on mine and shook his head slowly. “I don’t know, at least not yet,” he whimpered. Suddenly his eyes took on a serious look. “Did you know that some insects, termites, and ants mostly, will reabsorb their eggs if they feel that conditions aren’t favorable for their young?”

I shook my head, but before I could say anything he continued. “There are mammals that can hoard sperm and delay fertilization, others can delay implantation in the womb. If conditions get really bad, some animals will even eat their own young.”

I had no idea where he was going with this. “We’ve all done things we aren’t proud of. Things that were necessary,” I gestured at his arm, “to survive.”

He looked down at the tattoo and pulled his sleeve down, ashamed I thought. “I wish I could say that was the beginning or the end of things, but it wasn’t either. It was just another stop on an incomplete life filled with disappointment.”

“Do you want to talk about it?” They always want to talk about it. It’s why they are here – pretty face, a friendly voice, a sympathetic ear – for some it’s worth any price.

He didn’t even nod, he just started speaking, and I settled in for the long haul. I didn’t expect him to say what he said next.

“My first memories are from 1933. There was a student, Jerzy Zynger, a Polish Jew who had come to Miskatonic University to study microbiology. It was Zynger who had opened the crates that had been sitting in the back of the museum undisturbed for a year. The Antarctic Expedition had not gone well, there had been casualties, concerns about the samples they had brought back, and concerns about contamination, infection, and about invasive species. It had been thought best that the collected specimens should remain in storage.”

“Zynger had other ideas. He cracked open one of the crates, then he cracked open some of the things inside. Inside there was something black and moist, with pseudopods and a rudimentary intelligence. It oozed out of its million-year-old spore and then launched at Zynger’s face. Zynger tore at it with his fingers but it just oozed around them. He kept his mouth shut and closed his eyes too, but it found its way in through his nose, and then into his brain. In a matter of minutes what had once been Jerzy Zynger ceased to exist, and I stood there in his place. I had all his memories, all his skills – but I was so much more, and I knew it. Not many people know what a shoggoth is, but I did, I knew. The idea had been programmed into my very genetic material by the very things that had made me. Shoggoths, monstrous, protoplasmic engines that lived to serve the ancient and alien things that had once ruled this world, and I, I was not one of them. I was something else, though closely related – the word was ghorth – a kind of planula, a creature whose sole purpose was to feed, and to grow the spores of true shoggoths, and when the time was right, to spawn – to spread those spores across the vastness of the planet. They had to be spread so that they could feed and grow, isolated from each other, so that they didn’t follow their baser instincts and devour each other. Ghorth had some of the same characteristics as shoggoths, they were both metamorphic, though the ghorth to a much lesser extent. Where shoggoths could freely transform themselves into other shapes, the ghorth would only ever have the appearance of whatever lifeform it first bonded with. For all my days I would look like Jerzy Zynger. ”

“I fled Arkham that very night. By the next day, I was bound for England, and within the month I was back in Poland. Zynger was from Bialystock but I couldn’t go back there, friends and family might recognize problems in my behavior. My impersonation was good, very good, but not perfect, there were things I had to change. I had to put on weight both to feed the spores and to house them. This was easier to do in Warsaw, where I was just another face amongst the urban masses. I found work as a chemist, an easy occupation for one with my education and skills, and there were certain benefits to knowing who in the neighborhood was ill. On more than one occasion I tampered with the medications of my sickly patients and eased them on their way. I fed on these bodies of course, careful to avoid the organs where my poisons might accumulate, and I stole from them as well. Warsaw was not a cheap place to live. But I made do, I had no real need for the creature comforts or any plans for the future. By 1937 I could feel the spores growing inside me and knew that it was only a matter of time, a few years before they were seeded and ready to be sowed. I paid no attention to the politics of men, they didn’t matter to me. I was too young, too naïve. I couldn’t imagine how the machinations of men could interfere with the grand destiny that had been programmed into me in eons past.”

“But just because I couldn’t imagine it, didn’t mean it wasn’t true. In 1939 the Germans invaded, and by that fall I had become one of many imprisoned in the Warsaw ghetto. I did what I could, what I had to, to survive, to maintain my brood. But in the end, it wasn’t the lack of food that ended my gravid status. No, that was my capture and deportation to Treblinka. There amongst the human skeletons, I was an oddity, a man who still had some fat and muscle on his bones. The other prisoners thought me weak for breaking down into tears. They thought I was crying out of despair over our imprisonment. I couldn’t tell them the truth. Without a way to disperse them, the spores couldn’t hatch, and they reabsorbed back into the flesh of my system.”

“Soon I succumbed to the same horrors that my fellow prisoners had suffered. In months, the bulk that I had spent years accumulating was gone, and the human façade that I resided in was little more than a shadow of itself. It wasn’t I who organized the escape, but I certainly took advantage of it. I was stronger than my fellow prisoners, and more supple too. I should have taken advantage of my abilities earlier, and escaped the NAZIs and Germany long before it had become too late. Would have, should have, could have. Instead, I slipped into the woods surrounding Treblinka and kept moving south, feeding on whatever I could. Humans have such strange food limitations. Some of this is driven by biology, but mostly it’s driven by social taboos. Insects and vermin are forbidden, except in the most desperate of situations. But in war, surrounded by death, such creatures flourish, and I found the larder of war-torn Europe well stocked, as long as one was willing to broaden one’s palate. I have read stories that some isolated communities had resorted to cannibalism, devouring weakened refugees and even wounded soldiers. I cannot deny that when the opportunity arose, I too did such things – soldiers, men, women, the old and infirm, but never children – never, ever children. I am not a monster.”

“At the end of the war I made my way to France, and then with thousands of other Jewish refugees, I boarded a ship and made my way to Havana. I was still Jerzy Zynger, but my forged papers had sliced twenty years off my age. I thought perhaps that I might be recognized but I suspected that almost everyone I had ever known was dead – killed by the NAZIs. There were a few people at Miskatonic University who might recognize Zynger, my fellow students, and perhaps a professor or two, but they were thousands of miles away, and I was no longer a microbiologist. I found work as a diamond cutter. Once more I set about nurturing the gravid cells that would one day burst from my body. All I needed was time, and when the time came, the freedom to move about, leaving my deadly spawn in my wake.”

“I was more careful this time and made sure to align myself with Batista when he came back from Miami and took power. Cuba became a corrupt paradise, and I began making jewelry for the Americans who came to gamble at the Tropicano and the Hotel Nacional. I once had coffee with Luciano, and Kennedy bought a ring from me for some island girl he wanted to bang. I grew fat from the money spent on my art, and people thought me soft, and I knew that they whispered terrible things about my vices. Some thought me a homosexual; others suggested I was an SS officer hiding under an assumed name. A few thought I was both. A rare few accused me of gluttony. None suspected the life that was growing inside me, or that I was biding my time to destroy them all. I even set a date for the apocalypse, April 17th, 1960 – Easter. I thought it ironic, and whenever I thought of it, I chuckled to myself.”

“The rebels poured out of the mountains in late 1958. Even then we didn’t take them seriously. But then the general populace joined the fray and by January Batista had fled to Haiti. Foolishly, I stayed, I thought I could weather the storm in place, at least until my maid stopped showing up and the sound of gunfire echoed from down the street. I fled, a suitcase full of money at my side. I tried for the airport, but the roads were filled with people of similar minds, and the battlefront crept closer and closer. I took a side road trying to make it to the harbor, but the battle closed in around me. I cut through a field of tobacco, mowing down the stalks like a scythe. I only got so far before the plants jammed the axle and it snapped like a tree branch. I ran on foot, following farm trails over hills and through forests. I thought for sure I would make it. The docks were just over that crest I said to myself over and over again. I would find a boat – buy passage to Key West. I would be free, free to carry out my biological imperative.”

“The ragged band of soldiers that waited on the quay had other ideas.”

“I was arrested, and my suitcase full of money was seized, it branded me an enemy of the people. I was charged, with what I was never sure about, but it didn’t matter. In January 1959 I was thrown in prison. I didn’t see the sun or humans for eight weeks. I think the guards were surprised when they found me still alive, emaciated and dehydrated but still alive. They fed me and gave me fetid water, and then threw me in jail with the other political prisoners. I didn’t see the sun for eighteen months. And somewhere along the line my spores, my precious spawn, died once more.

I settled in, accepted what was done, and bided my time. They couldn’t keep me in prison forever. There would be another opportunity, another cycle – twenty years meant nothing in the great scheme of things.”

“I was wrong.”

“They held me for the whole twenty years. They fed me – all of us really – nothing, they expected us to starve, to die from dehydration, to succumb to disease or old age. I lived on condensation, and palmetto bugs and rats. Occasionally another prisoner would die, and I would drag them to a secluded spot and devour them whole. In twenty years I ate twelve men. Don’t look at me like that, they were dead already. I wasn’t going to waste the protein.”

“It wasn’t until April 1980 when the doors of my prison were opened and I along with hundreds of others were herded on to busses. I didn’t know what was happening, and it felt much like the train cars to Treblinka. But then we were at Mariel and there was a fleet of ships and thousands of people. We crammed onto the deck of a trawler – the stink of humanity and rotting fish was overwhelming. In hours we were in Key West, and I was free to roam the Earth once more.

It took time. I worked at losing the accent that I had picked up in Cuba and lost the tan. I changed my name – Jerzy Zinger became Jerry Singer. I shaved more time off my birthdate. I broke ties with the Cuban community but settled back in with the relatively more reclusive Jewish society. I bought a boat and ran fishing charters out of Miami. By 1985 the fishing business was little more than a front. I was smuggling cocaine from Haiti on twice-a-week runs. In 1987 I almost got caught and had to sink my own boat before the Coast Guard caught up with me. There were charges, but nothing ever stuck. I bought another boat and six months later began catering to the movie industry. My boat, the High Seas, can be seen in Nightmare Beach, a cheap Italian slasher flick. Most of my money came from using the High Seas as a set for porn shoots, and yes, I filled in as an actor from time to time. Until one of the actresses noticed I was starting to put on some flab around the middle.”

“I sold the boat in 1994 and bought a little place on a road out in the middle of nowhere. You won’t find Speck on any maps of Florida, and that was the point. The cracker box home on the canal next to the swamp was all I needed. Between groceries, fish and whatever wandered out of the swamp I was well-fed. By 1998 I was quite the specimen. I checked my weight at the local Winn-Dixie and I was more than three hundred pounds, most of it spores. At night I dreamt of flying cross-country and leaving a trail of my children in my wake.”

“I spent almost a year researching the best manner in which to travel. I would, of course, start out of Miami, and then up to Atlanta. From there I Would visit Boston, and then New York before heading west to Chicago, and Los Angeles beyond that. I debated heading south to Mexico, but instead decided to head across the Pacific to Tokyo and then Hong Kong. Then I would move on to Australia and Africa. It cost me a fortune. Citing my weight, I had the travel agent book two seats. She thought my plans rather queer and suggested there were better and more direct flights that I could choose. Spending just a few hours or a day in each city made no sense to her. I threw money at the situation, and she shut her mouth and did what she was told.”

“It was early Tuesday when I clambered into the van I had bought for the sole purpose of taking me to the airport. It was used and burned oil, but it was clean and it ran. It wasn’t likely to draw any attention. I got to MIA at 8:30, more than an hour before my flight. I wandered through the parking lot without really paying attention to what was going on around me. I had no bags so I made my way down the vast hallways to my gate, found a pair of seats that would accommodate my girth, and then settled in to wait for my boarding call.”

“There was a crowd of people gathered under the TV. It was tuned to CNN. The scene was of the New York skyline. One of the Twin Towers was burning. The scene shifted and they showed a commercial plane fly directly into the other tower and a mushroom of flame and smoke exploding behind it. September 11th, 2000. I never even got to see my plane.”

“I waddled back to the van. It was by sheer force of will that I was able to hold myself together for the drive home. It was only after I pulled into the driveway that I felt the mass inside me liquefy. I grabbed my belt and held my pants up as I fled the car a trail of jellified flesh leaking behind me. By the time I got inside the house, a chain reaction had taken control. I collapsed in the foyer in a wave of thick protoplasm that washed around me like a broken water balloon.”

“That was almost twenty years ago.”

He pushed back from the bar and ran a hand over his fat round belly. “It’s not like before, it’s a small batch, but it will still be enough. I still have a few months to gestate. But this time I’m prepared. The United States is the safest and freest country in the world. Six months from now I’ll be boarding a plane and spreading my seed around the country. Nothing can stop me this time, not as long as the planes are flying and the people are wandering about doing their day-to-day chores. I will spread like the infection that I am, and not even you knowing what is going to happen can stop it.”

He drained his glass and smacked his lips. “I am going to miss this world.” Then he wandered out the door and it closed with an ominous clunk.

I walked over and locked it behind him. For a moment I thought about what he had said and then shrugged. We get all sorts in the bar, one nut job was no worse than another. I went into the back and rolled out the mop and bucket. While I half-heartedly scrubbed the floor I watched the late-night news. It was December 2019 and BBC America was talking about a flu outbreak in Wuhan, China.

I turned the TV off and closed up for the night.

It’s been more than eighteen months, since my daughter has been born, and I’ve been triple vaccinated. It took me a long time to find Jeremy Sang. He’s lost weight, but it’s him. He doesn’t even live five blocks from the bar.

He might just be a crazy old man. There’s nothing to prove that he isn’t. He’s been through a lot, and I do feel sorry for him – the best-laid plans and all. The monster thing – the ghorth – just might be his way of coping. He could just be a lonely old man telling scary stories in a bar, for attention.

But I can’t take that chance.

If he is what he says he is, then sooner or later, things might go right for him, and if he is some sort of monster then he will succeed in spreading his spawn over the world. I really hope he is the horror he said he was.

Otherwise, what I’m about to do would be insane, criminal even.

I hope he burns quickly; I hope two cans of gasoline are enough.

Pete Rawlik is a writer living in Florida where he collects Lovecraftian fiction and works on environmental issues surrounding the Everglades and related ecosystems. His research for a pseudo-history of the Miskatonic River Valley laid the groundwork for what would eventually become Reanimators (2013), The Weird Company (2014), Reanimatrix (2016), The Peaslee Papers (2017), The Miskatonic University Spiritualism Club (2021) and The Eldritch Equations (2022). His short story collection, The Strange Company and Others, was released in 2019. He has edited two anthologies one with Brian Sammons, Legacy of the Reanimator (2015), and The Chromatic Court (2019) a collection of Lovecraftian stories inspired by the King in Yellow. He is a regular member of the Lovecraft Ezine Podcast and a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Science Fiction.